Story

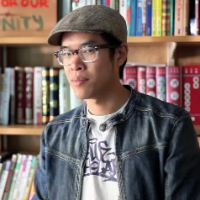

Kelly Tsai

On Change Over Time

On Her Experience at the Seattle Summit, 2001

Robert Karimi

Organizer (Seattle 2001 & Chicago 2003)

On planning multiple Summits

On planning multiple Summits

I was the undercover brother who knew both The Tongues and Isangmahal. Folks from Isangmahal came to my reading at the Seattle Poetry Festival and at the dinner after asked me my thoughts about the Summit. Anida had already broken the idea down to me, so I served as like the Ambassador of Love or matchmaker that just said, “Hell ya. Y’all should do it.” I attended that Summit, the one in Chicago, and the ones in Boston and Minneapolis. I was on the planning committee of Chicago, hosted events in Chicago, taught a crazy class with Ed Bok Lee, threw a crazy post-Summit party at my house in Chicago, was on the National committee during the craziness with New Orleans, and was on the planning committee for Minneapolis/St. Paul.

I got involved because it just made sense. My art is my activism. They are intertwined. The idea of bringing together artist/activists to talk about issues, build community, and perform in front of each other was exciting to me. Also, I had been performing for 8 years at the time, and really didn’t feel a sense of community in Poetry Slam, as I did with the folks like Isangmahal and the Tongues. And when you are half Iranian/Guatemalan and doing Spoken Word, you have to find your community where you can get it.

I got involved with planning because I was in Chicago, and I was the Artistic Director of the Guild Complex at the time. I wanted to use my resources to help out; also, it was a great team of people. I was living in Chicago, and I wanted to be a good host, and continue the good feelings from Seattle.

I never really cared for the Summit to come to my town. I know how hard it is to host one. The Summit always ends up where I am at, tho. 🙂

P.S. Another reason I feel the Summit was important: The Tongues were at the height of their popularity and they didn’t decide to become ballers, they wanted to use that energy to bring people together (without getting paid for it!). No one in Spoken Word has ever done that!

Bao Phi

On planning the Minnesota Summit, 2011

On planning the Minnesota Summit, 2011

Prior to Summit, many of us Asian Am spoken word artists would meet here and there, usually through slam, but we didn’t seem to have an opportunity to pull all of us together on our own terms. I’m pretty sure it was either a call or email from Anida, who was in Two Tongues at the time, who said they and Isangmahal were planning on organizing some type of summit or conference for APIA spoken word artists. From there, I think there were some group emails, plans on how to get Minnesota people to Seattle, and me and Ed were asked to teach a workshop. That was the first Summit – i’ve been involved, in various capacities, ever since, and i’ve been to every Summit. 2011 Summit in Minneapolis was important because Summit usually melds to fit the character of each city and each organizer, and we really wanted to 1) put a strong emphasis on the activism aspect of Summit and 2) make sure we combined that with melding community engagement that benefited, and was shaped by, local Minnesota activism.

For Minnesota APIA activists, we feel that there is a certain invisibility around our issues. Meaning, we don’t get a lot of national support. So we made sure, for our Summit, that we worked hard to immerse Summit participants in local APIA activist issues. That meant working closely with the Fong Lee family, with MN-based relationships like the one between former arts group Asian American Renaissance and Mizna, etc, and we wanted to incorporate on the ground, grassroots community activities. Also, approximately half of our core organizing committee identifies as queer, and we were made up of Southeast Asians, mixed race people, Adoptees, South Asians, etc, which I think is emblematic of APIA organizing in the Twin Cities. I don’t mean to infer that we were better than past Summits – what we tried to do, is go back to Summit’s past histories of community activism and make sure Summit participants engaged and valued local Minnesota APIA communities and organizing.

Giles Li

On his experience at the Boston Summit, 2005

On his experience at the Boston Summit, 2005

At the end of the family showcase we were running over time. We had to leave Northeastern, we had to get to Chinatown because we were throwing an after party in Chinatown. So we got the whole, I think there was six, no more than ten that had to go and weren’t able to go at Northeastern, so we moved them all to Golden Leaf in Chinatown which was historically—the building is still there but now but it isn’t the Golden Leaf—so we did that and finished the show there and we had everybody, everybody who hadn’t gotten the chance to perform there, and then we went right into a party. And it was actually at that party where I asked all the guys—because I was getting married next year, that next summer—so that was there I proposed to all the guys I wanted to be in my wedding party as groomsmen. I couldn’t talk to them before the Summit was over because I was too stressed out so it was at that party that I actually got to talk to them, all those guys, the five guys who ended up being my groomsmen were at the Summit. So you know, it was there that I finally felt like I had officially closed a chapter. I closed that Summit chapter and I was opening the chapter into planning getting married and that next chapter of my life so it was like an actual transition phase for me, a life transition.

Giles Li, on the impetus behind the Summit

[In] this current wave of Asian American community based arts that we’re riding right now…there’s Asian American arts viral, a lot of high profile, well produced art that’s being created by Asian Americans that has a general consciousness about it even in the American mainstream nationally, maybe internationally, but there’s also a less mainstream but still somewhat connect Asian American arts scene, that is more rooted in, communities that are, more rooted in a social justice community, an empowerment movement that is parallel to the mainstream viral video thing that’s happening and it’s not antagonistic. It’s something that happens alongside of that and they inform each other to some extent, but it’s a separate thing. And I think that strain of Asian American community based arts is, the Summit is a big piece of it. The Summit is the backbone of it.

Just like with anything, ten years into [the Summit], it means something different to someone who’s coming into it for the first time ten years in than someone who’s coming into it in its first year. Not in a bad way, just in a natural evolution kind of way. And I think that a lot of the things that have happened over the past ten years or whatever it is, more than ten years now, have changed the way that people perceive the Summit. There are definitely things that have changed about it, there are things that change about it from year to year, but as long as these values stay in tact, and as long as every Summit honors what has been always honored at the Summits before, that’s the important thing.

As it becomes easier to imagine a career in spoken word—in 2001 there was no career in spoken word, like there was no way you could have a career in spoken word where that would be your job for the rest of your life, it just wasn’t really feasible– business is a big part of it. It may be the primary part of it really, depending on how you look at it. And I don’t judge that negatively in general, but as far as the Summit is concerned, I don’t think that show biz has a place at the Summit. I don’t have any problem with people getting paid to do spoken word, I get paid to do it, I would like to get more. I think that people should get as much as they can out of spoken word, and even if your motivation is money that’s fine, but it can’t compromise, as far as the Summit is concerned, I wouldn’t want anyone to go to the Summit thinking it will boost their career.

Anida Yoeu Ali

On her experience at the Chicago Summit, 2003

On her experience at the Chicago Summit, 2003

The second Summit, it was very intense because it was a bigger Summit [than the first one in Seattle], but we were all experts in the area. It was good that we kept it this small group of four people because we were really good at what we were doing.

There was something that happened in Chicago that was unplanned, the moment that brings everyone together and wakes the community up. We were in the middle of the first night’s showcase and there was a young poet who went up. She had done a piece on incest and molestation by a caregiver when she was a young toddler and young person. And she just took the stage and let it all out. It was a huge cathartic moment for her, and it went on for a while because she needed it and we weren’t going to cut her off. The whole audience was crying with her. She was basically indicting the community and her family as part of what happened to her. She really put a stop to everything because we needed to stop. The whole community, the audience, everything needed to stop, to feel some of the real issues that folks were dealing with. It was also a really powerful moment because as organizers we needed to make a really fast decision. The audience was traumatized, she was traumatized, there was no way we could go on with the show. We stopped the show and brought everybody on stage and Jenny Lim was our keynote speaker, she led a healing circle and that became that night’s main event instead of it being this big glitzy showcase where everybody got to do their two to five minute poem, we stopped there and huddled and spoke and were silent, and all these things that for us, showed symbolically that we were there for this young woman and the community was going to go through it with her.

That moment [was also important] because she needed the community to follow through, and check up with her because it was such a big thing for her to be holding on her shoulders. So that example, again, those are the things that happen at the Summit that you don’t see in the archives, but are meaningful moments where you go “God, this shit is real. People really hold horrific stories just as much as the beautiful stories.

On the impetus behind the Summit

The Summit is about taking a breath and a moment together as a community, and celebrating that moment with each other through the power of spoken word poetry and that’s spoken word poetry that’s reflective of Asian American and Asians in America. I would extend that to include Asian Americans not in America because recently with our experiences with the deportation and the diaspora people who are Asian Americans, who are exiled and are part of the fabric of Asian America. But in its essence it is simply that. It is a gathering of one moment where people can finally see other people… in their own struggles for justice and visibility… and that there are incredible APIAs around the country and across the globe similar to what you are doing, what you’re striving for. IT’s not just to tell your story, but to tell your story in such a way to move your community forward in a way that pays homage to the continuum of Asian American history.

It was really important for folks to realize that they weren’t alone in the city or the area or region they were in. Some folks came even from the Pacific Northwest and didn’t even realize there were people in Portland, let’s say, and that things had happened. They were like “What? I thought I was the only one”, but then there’s another one. There’s two of you!… We’re rolling in deep…There were people from the LA area who had no idea that there was even a scene and all of a sudden they’re like “Wow, now I’m tapped into it.”… especially with the Bay. The Bay was a really disparate group and I really believe the Summit helped to put the Bay area APIA spoken word artists together.

The Summit is a place where you can finally see a piece of yourself reflected in others, in Asian Americans who are not only telling their story but trying to create a larger impact, in the world, in terms of issues of social justice or issues of invisibility. It’s that these folks who come together are not just there to tell stories. They realize they are part of a historical continuum of Asian Americans who have been fighting for a really long time on issues of justice and visibility and human rights. And that’s what’s different about this, at least the vision that I have for the APIA Spoken Word Summit, that it’s not just spoken word poets who are just telling their story. It’s so much more because all of those people who are gathered have a stake in the world.

Maya Santos

On planning for the Seattle Summit, 2001

On planning for the Seattle Summit, 2001

Why did I get involved in planning for the Summit? It was definitely a shared vision that we had with Anida, Marlon, and Joe. And the other folks in Isang Mahal that were part of the conversation. We felt really passionate about a space that was needed, or the space that was emerging, not just in Seattle and Chicago, but within all our networks, too. There were so many things happening, that it had to be done. We had to bring the network together so that people can feel more supported, you know, and recognized. This [was] a strong moment in history for us, we were feeling like it was our creative expression, as artists, poets, we really believed it was helping affect positive change by opening up a space for people on the margins to speak out, or express themselves and be creative about it.

At that time Isang Mahal was doing college conferences and stuff. We would be invited to perform, and that was how we met Two Tongues, at one of those performances on the college circuit. In a way it was all of these conferences in the college age range, where they would do all these events and they would include poetry. It was an outlet. It was the natural emerging of this space.

Because we were so plugged into the circuit, the whole poetry scene, and everything Asian American going on…It wasn’t hard to get people to know about it. It was harder to get people there, I think. We tried to make the Summit really affordable. We organized the housing and tried to keep a low registration and all that stuff.

On her experience at the Seattle Summit, 2001

I think it was a total high the whole time. What stood out was definitely the things we never planned for, which was having an open mic spill out into the street and the police coming, but sort of, just watching us because it was such a scene. And people getting into a group hug and crying, and it was really a love fest, in a way, people finding each other, finally, you know? Like a family that finds each other finally, that was the feeling. And finally being able to say things out loud and be heard and understood. And I remember taking the group photo in Chinatown, and I’m organizing, and you work and don’t look up sometimes, but then that moment I remember looking up, looking at everybody, and it was so crazy. It wasn’t like it was huge, it wasn’t about the numbers of people there, more like the feeling that everyone had in their own way, this feeling of home with each other that was amazing, something I’d never experienced at that level before.